This spring, Philip Mould & Company will shine a spotlight onto a group of exceptional Elizabethan and Jacobean portraits that have benefited from the very latest developments in a formerly dark age of British art history.

In recent years, a new generation of art historians has benefited from improved access to unseen or overlooked documentary sources and transformative technological advances in the physical understanding of art, to produce fresh insights into the life and work of many of the artists of this era, shedding new light on their painting practices and the production of portraits in 16th and early 17th century Britain. This emerging period of art history is one that has a global fascination, with forthcoming major exhibitions planned worldwide.

This free exhibition of 17 works – featuring such luminaries as Nicholas Hilliard (c.1547-1619), George Gower (c.1540-1596), William Larkin (c.1580-1619) and Isaac Oliver (c.1565-1617) – can be physically seen at the Philip Mould & Co gallery on London’s Pall Mall, or online at www.philipmould.com. It is accompanied by a comprehensive catalogue packed with brand new research. All the works in the show were discovered by Philip and his team, with the majority now in private collections, in the UK and overseas.

Philip says: “As a company we have been highly active over the last thirty years in the pursuit of undiscovered or overlooked early paintings, and where possible adding to the canon of knowledge – in fact, I like to describe art dealing as the archaeological arm of art history. This period is very special to me as it provided a turning point in my career, when in 1990 I discovered the lost and only recorded contemporary portrait of Henry VIII’s elder brother, Prince Arthur, which today hangs in the collection of Hever Castle in Kent.”

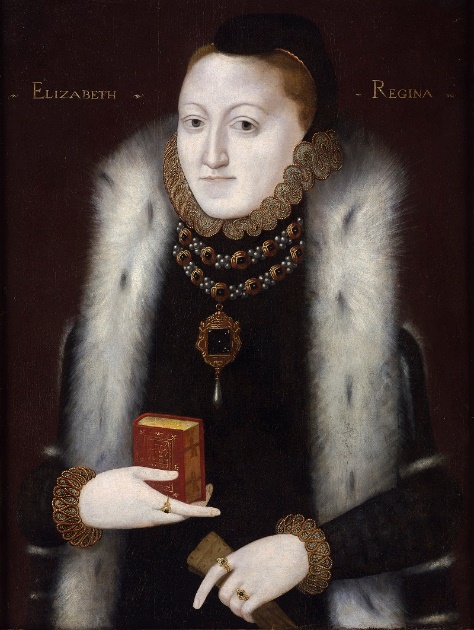

Portraits of this period are rich in iconography, and one of the undoubted highlights of Love’s Labour’s Found will be the chance to examine two depictions of Queen Elizabeth I; one from the start of her reign (1558-1561) and the other created more than 30 years later (1590s), both by unknown artists working in England. Elizabeth was acutely aware of the power of portraiture and used it shrewdly in the later years of her sovereignty to project an image of strength and authority. These later ‘Gloriana’ portraits are characterised by their opulence, a visual feast with Elizabeth’s costume dominating a composition saturated with colour and detail. This work stands in stark contrast to the one from the beginning of her rule which shows far greater restraint – she is portrayed in a simple black costume with an ermine trim, holding a pair of gloves in one hand and a prayer book in the other. This portrait is one of small number of surviving images that show Elizabeth I at the outset of her reign, a surprisingly un-regal portrait and were it not for the well-established dating, one might find it hard to believe that this austere looking young woman had just acceded to the throne of England.

Standing adjacent to Elizabeth – very much as he did in life, albeit becoming the subject of great suspicion and intrigue due to his relationship with the Queen – is a portrait Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester. Dudley was one of the most prominent figures of the Elizabethan age and a highly influential patron of the arts, and one of the most painted men of the day (in fact, he was possibly painted more times that the Queen herself). The painting in the exhibition appears to be a product of the Steven van der Meulen workshop from the early 1560s, and a full discussion of this formerly misunderstood artist is explored in the catalogue. Glamourous and courtly in demeanour, Dudley wears a red doublet of taffeta or satin and a buff-colour peascod jerkin, cut and laid with gold lace, with a high collar and small shirt ruff, his red hose is both padded and boned, complete with a discreet codpiece. On a gold enamelled chain set with pearls around his neck is the ‘Lesser George’ of the Order of the Garter.

Elizabeth’s successor is also represented in the show. A strikingly imperial and propagandist portrait of King James VI & I was painted not long after his accession to the English throne (1604, Unknown Artist) and is unique within his documented iconography in oil paint. Its visual elements reveal a ruler’s message of union and peace which would not have been lost on an educated contemporary audience.

16th-century portraits of children are rare, but an exceptional example is included in Love’s Labour’s Found – A Young Girl (Unknown Artist, 1595). When children were portrayed in this period, the child’s maturity was often exaggerated, as is the case here with her intricately decorative, fitted gown which cinches in her narrow, idealised waist, her silhouette alluding to that of a grown woman, although we know she is only 4 years old. Thanks to an increased interest in the documentation and presentation of family lineage, the Elizabethan period saw a development in portraits which display precise information about the sitter – in this case, an inscription identifies the age of the young sitter; ‘Aetatis Suae 4’, in her fourth year.

Sumptuous costumes and lavish jewellery are a hallmark of Elizabethan and Jacobean portraits. William Larkin was one of the most accomplished portrait painters of the early 17th-century and his work arguably represents the zenith of ruff-clad, theatrically excessive likenesses that the period was capable of. A Gentleman (c.1615) is one of the latest additions to Larkin’s oeuvre and reveals his characteristic combination of subtle flesh tones, slightly dome-shaped physiognomy, and near-obsessive attention to detail in the ruff.

Elizabethan miniatures have often been viewed, to quote Nicholas Hilliard (c.1547-1619) – perhaps the most celebrated miniature painter of the period – as ‘a thing apart’. Directly descended from late medieval manuscript illumination, this art form involved painting tiny, watercolour portraits on wafer-thin sheets of calf skin, using brushes made from squirrel hairs set in bird quills, mounted on wooden sticks. Hilliard went to great lengths, not least in his Arte of Limning – one of the first treatises on the visual arts written in English – to position miniature painting as superior to other forms of visual representation.

This exhibition showcases two very different miniatures by Hilliard from the 1590s, which highlight his continued artistic experimentation. Hilliard was inspired to innovate by the success of his former pupil, Isaac Oliver (c.1565-1617) – also represented in the show with Lady Dorothy Sidney, c.1615 – who had become his leading competitor. Oliver’s rich, Italianate chiaroscuro, contrasted with Hilliard’s stated preference for clean lines and little shadow, prompting the older artist to introduce a greater degree of naturalism to his work. A Gentleman, wearing black doublet and white lace collar, against a red curtain background is also one of the first occasions Hilliard used a red background painted to simulate velvet, rather than his traditional vivid blue backdrop.

The exhibition also offers the very first opportunity to see the most recent discovery by Philip Mould & Co, a very rare portrait of Henri III, King of France (1551-1589), by Jean Decourt (c.1530-c.1585) just 57mm tall. Originally thought to be a miniature of Sir Walter Raleigh, it was finding the signature, ‘Decourt’ along with the date ‘1578’, on the reverse when the conservator opened the painting’s delicate frame that confirmed the artist’s true identity. Unusually, despite Decourt’s high profile as a renowned artist to the French court (including his role as portraitist to Mary, Queen of Scots), no signed portrait had previously been unequivocally ascribed to this highly significant artist, until that remarkable moment.

Philip Mould says: “This is the latest in a series of exhibitions spanning the last few decades that seeks to combine the paintings we have had the privilege of handling with the highest quality cataloguing of which we are capable. As we all emerge from lockdown and are able to visit art galleries once again, I hope this exhibition will provide a visual treat for visitors and also intrigue them about a period of art history where there is so much more still to discover.”